ACL Reconstruction

KNEE PROBLEMS

SURGICAL PROCEDURES

Introduction

|

|

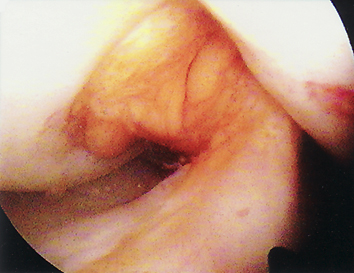

| Arthroscopic view of torn

anterior cruciate ligament |

Few musculoskeletal conditions have stimulated as much controversy, debate, and research as injury to the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL). Once considered the beginning of the end of normal knee function, the current prognosis of ACL injury, with appropriate treatment, appears to be much better. ACL surgery and rehabilitation have undergone dramatic changes over the past decade, due to extensive clinical experience, improved surgical techniques and better understanding of rehabilitation.

Pre- and post-operative rehabilitation is a major factor in the success of ACL reconstruction. Early restoration of full joint movement and weight-bearing are of paramount importance for successful rehabilitation. We aim to ensure a complete understanding of the basic principles of the ACL reconstruction, to restore the full range of motion, near normal strength and to mentally prepare the patient for the operation and accelerated rehabilitation.

The major goals of ACL surgery and rehabilitation are:

to restore normal joint anatomy, to provide static and dynamic knee

stability and return to work and sport as soon as possible. It is very

important that the patient takes an active part in the rehabilitation,

both before and after the operation.

About the ACL

The knee is a complex joint, which has the ability to bend and rotate slightly. Knee ligaments help control motion by connecting bones and bracing the joint against abnormal types of motion. The ACL links the back of the femur (thighbone) to the centre of tibia (shinbone), stabilising the knee, mainly in the forwards and backwards direction. In addition to its mechanical restraining function, the ACL provides important neurological feedback that directly affects perception of joint position, and reflex muscular stabilisation of the joint or so-called proprioception. Proprioception is the sense of the orientation of one's limbs in space and it is different from the sense of balance. Conscious and subconscious proprioception is essential for normal joint function in daily activities, occupational tasks and sports. Proprioception diminishes following capsulo-ligamentous knee injury, but is significantly restored following surgical ACL reconstruction and rehabilitation.

History

Claudius Galen of Pergamum and Rome (130 - 201 AD) must be given the credit for first describing the anatomy and nature of the anterior cruciate ligament. He recognized the stabilizing nature of the ligament and, when discussing the knee, he mentions the "genu cruciata". Source: Vladimir Bobic. Current concepts of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Surgery, November 1992.

ACL Injury

A typical mechanism of an ACL injury is a non-contact twisting movement, usually due to abrupt deceleration and change of direction. Non-contact mechanisms account for 70-80% of ACL tears. Side-stepping (cutting), pivoting and landing from a jump are examples of events that may cause an ACL tear. An audible pop or crack, pain and the knee giving way are typical initial signs, followed by almost immediate swelling, due to bleeding inside the joint. Associated damage to other important joint structures, such as collateral ligaments, menisci, articular cartilage, and subchondral bone is very frequent. Some patients achieve satisfactory stability and function with non-operative treatment (rehabilitation and adjustments to daily activities and sports). However, chronic ACL deficiency results in gradual damage to the menisci and articular cartilage and consequent early joint degeneration. Equally, although mechanically and functionally successful ACL reconstruction can reduce knee instability and the risk of subsequent re-injury, reconstruction does not guarantee a return to pre-injury knee function, nor necessarily prevent the development of joint degeneration.

Diagnosis of ACL Injury

An experienced clinician can diagnose as many as 90% of ACL tears based on history and clinical examination, but ACL injuries are still often missed. Clinical diagnosis of a complete acute ACL tear is relatively straightforward, although swelling, pain, limited range of knee movement and associated injuries (mainly of the medial  collateral ligament and the medial meniscus) complicate this issue. Clinical tests, including the Lachman's test, anterior drawer and pivot shift are often suggestive of a major ACL tear, especially if associated with symptoms of giving way and knee instability. Clinical examination may be difficult in large patients, in patients with strong secondary muscular restraints, and in patients with an acute injury and soft tissue swelling and guarding. Partial ACL tears are especially difficult to diagnose clinically. Some ACL deficient knees are initially stable clinically and remain stable and symptom-free especially if the MCL and both menisci are intact, and while the patient's activity levels remain reduced.

collateral ligament and the medial meniscus) complicate this issue. Clinical tests, including the Lachman's test, anterior drawer and pivot shift are often suggestive of a major ACL tear, especially if associated with symptoms of giving way and knee instability. Clinical examination may be difficult in large patients, in patients with strong secondary muscular restraints, and in patients with an acute injury and soft tissue swelling and guarding. Partial ACL tears are especially difficult to diagnose clinically. Some ACL deficient knees are initially stable clinically and remain stable and symptom-free especially if the MCL and both menisci are intact, and while the patient's activity levels remain reduced.

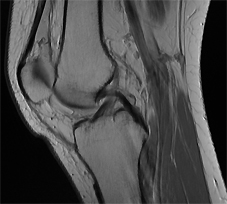

MR imaging (MRI scan) is a very detailed and reliable diagnostic tool, not only for ACL injury but also for injuries of other ligaments, meniscal tears, chondral, osteochondral and subchondral (bone bruise and bone marrow oedema) injuries.

Often, there is no correlation between the mechanism of the knee injury, symptoms, clinical tests, and MRI findings. Once the diagnosis of an ACL injury is established, it is important to start with appropriate rehabilitation as soon as possible and to re-examine the knee, as the clinical picture and symptoms often change significantly within a short period if time.

A few words about the Lachman test:

|

Video: Lachman's test Courtesy of Dr Don Johnson |

At the annual meeting of the American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine (AOSSM) in 1976 in New Orleans Joseph Torg, MD, presented a paper on "Clinical Diagnosis of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Instability in the Athlete". In addition to describing the Lachman test as a procedure preferable and much more reliable than the classic anterior drawer test he also reported on the frequency of injury to the anterior cruciate ligament associated with injuries to other structures. This study was subsequently published in the American Journal of Sports Medicine in 1976:

"John W. Lachman, MD, Former Chairman and Professor of Orthopedic Surgery at Temple University, Philadelphia, has for many years taught a simple, reliable, and reproducible clinical test to demonstrate anterior cruciate ligament instability. The examination is performed with the patient lying supine on the table with the involved extremity on the side of the examiner. With the patient's knee held between full extension and 15 degree flexion, the femur is stabilized with one hand while firm pressure is applied to the posterior aspect of the proximal tibia in an attempt to translate it anteriorly. A positive test indicating disruption of the anterior cruciate ligament is one in which there is proprioceptive and/or visual anterior translation of the tibia in relation to the femur with a characteristic "mushy" or "soft" end point. This is in contrast to a definite "hard" end point elicited when the anterior cruciate ligament is intact. When the anterior horizon of the knee is viewed from the lateral aspect, the normal slope of the infrapatellar tendon becomes obliterated. A corollary to interpreting the test is that if question remains in the examiner's mind as to whether the test is positive or negative, the ligament is torn". Text from:

- Joseph S. Torg, MD, Wayne Conrad, AB, Vickie Kalen, AB. Clinical Diagnosis of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Instability in the Athlete. The American Journal of Sports Medicine 1976, 4: 84-93. In addition to the first mention of the Lachman's test in a publication, this study was also the first to identify the frequent association of anterior cruciate ligament and meniscal lesions.

- Joseph S Torg, MD. Who is John Lachman? The John Lachman Society.

ACL Reconstruction

|

|

| ACL reconstruction with patella tendon autograft. |

ACL reconstruction is not an emergency operation. Delaying surgery until a full range of motion is obtained significantly reduces the chance of having problems post-operatively. Delaying acute surgery also allows the patient to be mentally better prepared for surgery and gives the patient time to learn, fully understand and practise adequate exercises.

A complete tear of the ACL has minimal ability to heal and often requires surgical reconstruction. This involves replacing the torn ligament, with the middle third of the patella tendon (bone-patella tendon-bone autograft) which is our preferred graft mainly because of the fixation strength. Fastening the graft to the bone with interference screws provides secure fixation which enables early accelerated progressive rehabilitation to take place. Surgery is followed by 1 to 2 days of hospital stay and by several months of intensive rehabilitation to restore normal range of motion, strength, flexibility and proprioception.

Although there are some concerns about patellofemoral problems associated with this particular graft we have not seen any significant long-term problems in our practice. We have not seen any evidence of accelerated wear and tear associated with this particular graft and this particular surgical technique. Most international articles, published in reputable journals, report equivocal mid- to long-term functional results of the use of patella tendon or hamstring tendon grafts in ACL reconstructions.

- YouTube ACL Reconstruction Animation, Bertram Zarins, M.D. Please note that our ACL reconstruction technique is similar but not identical to the animated technique. We do not use allograft tissue and CPMs

Further information on the choice of the graft for ACL reconstruction:

-

Bruce D. Beynnon, PhD, et al.: Anterior Cruciate Ligament Replacement: Comparison of Bone-Patellar Tendon-Bone Grafts with Two-Strand Hamstring Grafts. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (American) 84:1503-1513 (2002). Summary: "After three years of follow-up, the objective results of anterior cruciate ligament replacement with a bone-patellar tendon-bone autograft were superior to those of replacement with a two-strand semitendinosus-gracilis graft with regard to knee laxity, pivot-shift grade, and strength of the knee flexor muscles. However, the two groups had comparable results in terms of patient satisfaction, activity level, and knee function."

-

Herrington L, et al.: ACL reconstruction, hamstring versus bone-patella tendon-bone grafts: a systematic literature review of outcome from surgery. The Knee 12 (2005) 41-50. Summary: "The literature suggests that there continues to be much discussion regarding the ideal graft choice for ACL reconstruction. There are strong advocates for both PT (patella tendon) and HT (hamstring tendon) grafts, some suggesting that the PT provide better stability and others indicating lower incidence of PFP (patello-femoral pain) with the HT graft. The results of the 13 studies included in this review suggest that there is no significant evidence to indicate that one graft is more effective than the other. Both the PT and HT grafts appear to improve patients’ performance, and therefore both would be good choices for ACL reconstruction."

-

Liden M, et al.: Patelar tendon or Semitendinosus tendon autografts for ACL reconstruction: a prospective randomised study with a 7-year follow-up. The American Journal of Sports Medicine 35:740-748 (2007). Summary: "On the basis of the present study, we conclude that the results were acceptable using both types of graft at 7 years after surgery. No clear advantage for either technique was demonstrated. Both techniques are reliable when it comes to improving patient performance, allowing a return to a higher level of activity than before surgery, and are therefore equally valid choices for ACL reconstructions even in the long term. Contrary to previous short-term studies, we found no significant differences in terms of donor-site morbidity and laxity between the study groups."

- Leo A. Pinczewski, FRACS, et al.: A 10-Year Comparison of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstructions With Hamstring Tendon and Patellar Tendon Autograft. The American Journal of Sports Medicine 35:564-574 (2007). Summary: "It is possible to obtain excellent results with both HT and PT autografts. We recommend HT reconstructions to our patients because of decreased harvest-site symptoms and radiographic osteoarthritis."

ACL Tear: To Reconstruct or Not

AANA Newsletter, November 2010.

Point/Counter Point is a feature of the AANA's Newsletter where surgeons who have differing opinions are asked to discuss a topic. The topic in this issue is Surgical versus Conservative Treatment of ACL Injuries. In this Point-Counterpoint, Dr. Mitchell Drake and Dr. William Stanish make the case that many patients with ACL tears will do well without surgery, while Dr. Sabrina Strickland argues that results are better for many patients when they are treated with ACL reconstruction.

Further information on nonoperative treatment of ACL deficiency:

- Paul Neuman, MD, et al. Prevalence of Tibiofemoral Osteoarthritis 15 Years After Nonoperative Treatment of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury. The American Journal of Sports Medicine 36:1717-1725 (2008).

- Ioannis Kostogiannis, MD, et al. Activity Level and Subjective Knee Function 15 Years After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury: A Prospective, Longitudinal Study of Nonreconstructed Patients. The American Journal of Sports Medicine 35:1135-1143 (2007).

ACL Rehabilitation

Preoperative rehabilitation is extremely important for the successful outcome of ACL reconstruction. Regaining a full range of motion, strength and proprioception before the operation, especially full symmetrical hyperextension, minimises post-operative problems. Patients with an ACL deficiency, suitable for reconstructive surgery, are educated on the nature of their problem, surgical technique and peri-operative rehabilitation, by the surgeon, at the time of the first clinic visit. They are also visited by the physiotherapist, prior to the operation, and guided through an updated rehabilitation programme.

Our goal is to guide our patients through the rehabilitation without unnecessary restrictions. For an update on perioprative ACL rehabilitation please see our separate page on Accelerated ACL Reconstruction Rehabilitation program which was kindly written and put together by Mark De Carlo and his team at the Methodist Sports Medicine Center, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA.

Further information:

- Todd Arnold, MD, K. Donald Shelbourne, MD. A Perioperative Rehabilitation Program for Anterior Cruciate Ligament Surgery. The Physician and Sportsmedicine, January 2000. Please note that free access to this article is no longer available.

- Robert Johnson. Current concepts of rehabilitation following ACL reconstruction. ISAKOS Current Concepts, Winter 2007

Downloads:

- Chester Knee Clinic Guide to ACL Reconstruction Rehabilitation

- Aircast Knee Cryo/Cuff gravity cooler: cooling and compression postoperative device

Does ACL Reconstruction Prevent Osteoarthritis?

ACL injury, if undiagnosed and untreated, has been associated with disability, meniscal tears, chondral damage and arthritis in studies of patients presenting with chronic ACL deficiency. The goals of ACL reconstruction are to prevent recurrent knee injury, symptoms of instability and pain, sports disability, and to prevent or delay deterioration of the joint (radiographic osteoarthritis). The general damage to the knee (preoperative meniscal and chondral deficiency) has a significant impact on functional outcomes of ACL reconstruction and postoperative activity levels. Several observational studies have suggested that higher post injury activity is associated with a higher degree of radiographic osteoarthrosis.

Although there is no doubt that ACL reconstruction can reduce anterior knee laxity and the risk of subsequent re-injury, reconstruction does not guarantee return to pre-injury knee function, nor necessarily prevent the development of OA on follow-up radiographs. Controversy continues about whether ACL reconstructive surgery leads to OA, but equally there is no evidence in the scientific literature that ACL reconstruction prevents the development of subsequent OA.*

Further information:

- * Round table discussion, Part 1: Controversy continues about whether ACL surgery leads to OA. Orthopaedics Today International, January 2005; 8:1.

-

* Round table discussion, Part 2: Controversy continues about the impact of ACL reconstruction and postop rehabilitation. Orthopaedics Today International, March 2005; 8:24.

- Tina DiMarcantonio. ACL reconstruction carries higher risk of OA than nonoperative treatment. Orthopaedics Today International, Sports Medicine, July 2006: 9:6. Data from: Kessler MA, Behrend H, Rukavina A, et al. Function and osteoarthritis after ACL rupture: 12-year follow-up results after nonoperative vs. operative treatment. #SS-08. Presented at the Arthroscopy Association of North America (AANA) 25th Annual Meeting. May 18-21, 2006. Hollywood, Florida, U.S.A.

-

Cor P van der Hart, et al.: The occurrence of osteoarthritis at a minimum of ten years after reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research 2008, 3:24.

- Paul Neuman, MD, et al.: Prevalence of Tibiofemoral Osteoarthritis 15 Years After Nonoperative Treatment of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury. The American Journal of Sports Medicine 36:1717-1725 (2008).

ACL Reconstruction in Patients over 50

3 November 2008, AAOS Headline News Now

According to the results of a study published in the November issue of the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (British volume), reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) in carefully selected patients aged 50 years or over can achieve results similar to those in younger patients, with no increased risk of complications. The research team reviewed the records of 34 patients aged 50 years or over who underwent primary ACL reconstruction (35 knees) between 1990 and 2002. Overall, 23 knees were reconstructed with patellar tendon allograft, and 12 with patellar tendon autograft. The authors noted post surgery improvements in mean knee extension and flexion, Lachman grade, International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) scores, and Lysholm scores. Three graft failures (8.6 percent) required revision. Abstract:

- D. L. Dahm, MD, et al.: Reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament in patients over 50 years. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery - British Volume, November 2008, Vol 90-B, Issue 11, 1446-1450.

Page last updated on 12 May 2018

Site last updated on: 28 March 2014

|

[ back to top ]

Disclaimer: This website is a source of information

and education resource for health professionals and individuals

with knee problems. Neither Chester Knee Clinic nor Vladimir Bobic

make any warranties or guarantees that the information contained

herein is accurate or complete, and are not responsible for

any errors or omissions therein, or for the results obtained from

the use of such information. Users of this information are encouraged

to confirm the accuracy and applicability thereof with other sources.

Not all knee conditions and treatment modalities are described

on this website. The opinions and methods of diagnosis and treatment

change inevitably and rapidly as new information becomes available,

and therefore the information in this website does not necessarily

represent the most current thoughts or methods. The content of

this website is provided for information only and is not intended

to be used for diagnosis or treatment or as a substitute for consultation

with your own doctor or a specialist. Email

addresses supplied are provided for basic enquiries and should

not be used for urgent or emergency requests, treatment of any

knee injuries or conditions or to transmit confidential or medical

information. If you have sustained a knee injury or have a medical condition,

you should promptly seek appropriate medical advice from your local

doctor. Any opinions or information,

unless otherwise stated, are those of Vladimir Bobic, and in no

way claim to represent the views of any other medical professionals

or institutions, including Nuffield Health and Spire Hospitals. Chester

Knee Clinic will not be liable for any direct, indirect,

consequential, special, exemplary, or other damages, loss or injury

to persons which may occur by the user's reliance on any statements,

information or advice contained in this website. Chester Knee Clinic is

not responsible for the content of external websites.

Disclaimer: This website is a source of information

and education resource for health professionals and individuals

with knee problems. Neither Chester Knee Clinic nor Vladimir Bobic

make any warranties or guarantees that the information contained

herein is accurate or complete, and are not responsible for

any errors or omissions therein, or for the results obtained from

the use of such information. Users of this information are encouraged

to confirm the accuracy and applicability thereof with other sources.

Not all knee conditions and treatment modalities are described

on this website. The opinions and methods of diagnosis and treatment

change inevitably and rapidly as new information becomes available,

and therefore the information in this website does not necessarily

represent the most current thoughts or methods. The content of

this website is provided for information only and is not intended

to be used for diagnosis or treatment or as a substitute for consultation

with your own doctor or a specialist. Email

addresses supplied are provided for basic enquiries and should

not be used for urgent or emergency requests, treatment of any

knee injuries or conditions or to transmit confidential or medical

information. If you have sustained a knee injury or have a medical condition,

you should promptly seek appropriate medical advice from your local

doctor. Any opinions or information,

unless otherwise stated, are those of Vladimir Bobic, and in no

way claim to represent the views of any other medical professionals

or institutions, including Nuffield Health and Spire Hospitals. Chester

Knee Clinic will not be liable for any direct, indirect,

consequential, special, exemplary, or other damages, loss or injury

to persons which may occur by the user's reliance on any statements,

information or advice contained in this website. Chester Knee Clinic is

not responsible for the content of external websites.