Knee Problems: Ligament injuries

KNEE PROBLEMS

SURGICAL PROCEDURES

See Also:

Ligament Injuries

Ligament injuries usually occur from hyperextension or abnormal rotation of the knee and involve the collateral and cruciate ligaments. The main symptom of ligament injury is a sense of instability, either from side to side or forwards to backwards. Collateral ligament injuries are easy to diagnose, but cruciate ligament injuries are frequently missed and often misdiagnosed.

Collateral Ligaments

The collateral ligaments are located at the inner side and outer side of the knee joint. The medial collateral ligament (MCL) connects the femur to the tibia and provides stability to the inner side of the knee. The lateral collateral ligament (LCL) connects the femur to the fibula and stabilizes the outer side. Most collateral ligament injuries do not require surgical treatment. The treatment plan should be based on the level of instability, the patient's preinjury level of activity and motivational factors. Surgical treatment for isolated injuries of the MCL and LCL is a controversial topic.

Medial Collateral Ligament (MCL)

Injuries to the MCL are usually caused by contact on the outside of the knee and are accompanied by sharp pain on the inside of the knee. Contrary to most other knee ligaments the medial collateral ligament (MCL) has an excellent ability to heal, being fairly large and well vascularised structure. The vast majority of isolated medial ligament injuries heal without significant long-term problems. There is some variation in opinion among orthopaedic surgeons about the best way to treat medial ligament injuries, but the vast majority favour allowing them to heal without surgery. It is however important to recognise and treat acute medial complex laxity as early as possible. Most NSAID's seem to enhance the ability of the MCL complex to heal, up to 50%, if administered early. A one-week course should be started immediately, preferably within a couple days after the injury. The knee should not be immobilised in a plaster cylinder. Instead, a long, hinged brace should be used for 4 to 6 weeks. Short periods of restricted range of motion, but with full weight-bearing allowed, and physiotherapy are used instead. Recommendations for treatment include the following:

- Grade I: Compression, elevation, and cryotherapy are recommended. Short-term use of crutches may be indicated, with weight-bearing as tolerated.

- Grade II: A short-hinged brace that blocks 20 to 30° of terminal extension but allows full flexion should be used. The patient may bear weight as tolerated. Closed-chain exercises allow for strengthening of knee musculature without putting stress on the ligaments.

- Grade III: The patient initially should be non–weight-bearing (NWB) on the affected lower extremity. A hinged braced should be used with gradual progression to full weight-bearing (FWB) over 4 weeks. Grade III injuries may require 8-12 weeks to heal.

- All MCL injuries should be treated with early range of motion (ROM) and strengthening of musculature that stabilises the knee joint.

After satisfactory rehabilitation, many people resume their previous levels of activity. Appropriate rehabilitation is usually successful functionally, but, if the patient fails to progress with treatment, a meniscal or cruciate ligament tear should be suspected.

Further information:

- Thomas M DeBerardino, MD and Jeffrey C Gundel, MD. Medial Collateral Knee Ligament Injury. eMedicne article. Last updated May 30, 2006.

Lateral Collateral Ligament (LCL)

The LCL is relatively rarely injured. Tears to the LCL commonly occur as a result of direct blows to the inside of the knee, which can over-stretch the ligaments on the outside of the knee. The tear can occur in the middle of the ligament or at either end. LCL tears occur in sports that require a lot of quick stops and turns, such as soccer and skiing, or in sports in which there are violent collisions, such as hockey. Pain, stiffness, swelling, and tenderness along the outside part of the knee are symptoms of an LCL tear. The knee may feel loose and give way or it may lock. More severe tears can cause numbness or weakness in the foot. This happens because the peroneal nerve is near the LCL and may be stretched at the time of injury, or squeezed by swelling of the surrounding tissues. The LCL usually responds very well to non-surgical treatment. LCL tears do not heal quite as well as medial collateral ligament tears and some severe LCL tears may require surgery. Recovery time in general depends on the severity of the injury. Recommendations for treatment of LCL injuries include the following:

- Grades I and II: These injuries are treated according

to a regimen similar to that for MCL injuries of the same severity.

A hinged brace is used for 4-6 weeks.

- Grade III: Severe LCL injuries typically are treated surgically due to rotational instability since they usually involve the posterolateral corner (PLC) of the knee. Patients may require bracing and physical therapy for up to 3 months to prevent later instability.

- Grade III LCL tears usually involve the posterolateral complex and are associated with instability. These patients require surgical repair.

Further information:

- Adam B Agranoff, MD and Robert J Kaplan, MD. Medial Collateral and Lateral Collateral Ligament Injury. eMedicne article. Last updated: July 9, 2008.

- Meislin RJ. Managing Collateral Ligament Tears of the Knee. The Physician and Sportsmedicine, March 1996.

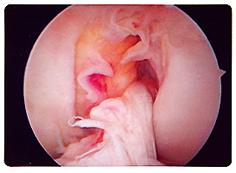

Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL)

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is one of the most frequently injured ligaments in the human body. Estimated incidences of 0.24 to 0.34 ACL injuries per 1000 population per year have been reported. Few musculoskeletal conditions have stimulated as much controversy, debate, and research as injury to the anterior cruciate ligament. Once considered the beginning of the end of normal knee function, the current prognosis of ACL injury, with appropriate treatment, appears to be much better.

A typical mechanism of an anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury

is a non-contact twisting movement, usually due to abrupt deceleration

and change of direction. Side-stepping (cutting), pivoting and landing

from a jump are examples of events that may cause an ACL tear. An audible

pop or crack, pain, and the knee giving way are typical initial signs,

followed by almost immediate effusion, due to bleeding inside the joint.

Associated damage to other important joint structures, such as collateral

ligaments, menisci and articular cartilage, is very frequent (over 50-70%).

A partially torn ACL usually does not require reconstruction.

A complete tear of the ACL has minimal ability to heal and often requires surgical reconstruction, as most patients suffer from functional problems, like giving way and instability. An ACL reconstruction is not an emergency operation. Delaying surgery until full range of motion is obtained significantly reduces the chance of having problems post-operatively. Delaying acute surgery also allows the patient to be mentally better prepared for surgery and gives the patient time to learn, fully understand and practise the adequate exercises. Regaining the full range of motion, strength and proprioception before and after the operation, especially full symmetrical hyperextension, minimises post-operative problems. ACL reconstruction involves replacing the torn ligament, usually with the middle third patellar tendon or hamstring tendon graft. Although most people benefit from ACL reconstruction in functional terms, approximately 10% of patients require a second operation, mainly because of the loss of motion, further meniscal injury and graft failure. ACL reconstructions are not very successful in the long-run in people with chronic meniscal and chondral deficiency.

Further information:

- Evans NA, Chew HF, Stanish WD. The Natural History and Tailored Treatment of ACL Injury.

The Physician and Sportsmedicine, September 2001. - Boden BP, Griffin LY, Garrett WE. Etiology and Prevention of Noncontact ACL Injury. The Physician and Sportsmedicine, April 2000.

- Ioannis Kostogiannis, MD, et al. Activity Level and Subjective Knee Function 15 Years After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury: A Prospective, Longitudinal Study of Nonreconstructed Patients.

The American Journal of Sports Medicine 35:1135-1143 (2007).

Posterior Cruciate Ligament (PCL)

Severe trauma is usually responsible for major PCL tears, which are

relatively rare in sports injuries. Isolated PCL tears do occur in sports,

but they are less frequent and less disabling than ACL tears. PCL tears

are often missed or misdiagnosed, and therefore probably more common

than once believed. Haemarthrosis is not a usual feature of this injury,

but bruising of the popliteal fossa and the calf is frequent. Most patients

do not have significant functional problems and do not complain of giving

way, which is a common problem in ACL deficiency and meniscal tears.

Most PCL tears are interstitial and heal with time, developing a firm

endpoint although in a lax position. Most people are able to return

to full activities with nonsurgical therapy. The specific rehabilitation

programme is not significant for the final result, but it can influence

the timing of return to activities. However, chronic PCL laxity causes

significant patello-femoral problems (anterior knee pain), because of

the chronic posterior translation of the tibia and increased pressure

on patellofemoral articular cartilage. Current reconstructive procedures,

irrespective of the choice of the graft, can not reproduce normal PCL

kinematics and have not proven better than nonoperative treatment. Generally,

PCL reconstructions are not yet as successful as ACL reconstructions

and the jury is still out as to what the best way to rehabilitate reconstructed

PCL's is. Long-term follow-up after nonsurgical management has revealed

that most patients rate the knee as good enough and are able to return

to sports.

Further information:

- Morgan EA, Wroble RR. Diagnosing Posterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries. The Physician and Sportsmedicine, November 1997.

Combined Ligament Injuries

One of the most common combined injuries is the MCL and ACL tear, which results from a lateral blow to the knee with the foot fixed. A more severe lateral blow can cause MCL/ACL/PCL injury. In two ligament injuries that involve both a collateral and a cruciate ligament, varus or valgus stress will demonstrate collateral ligament laxity, with no firm endpoint at 30 degrees of flexion. However, the leg will be stable in full extension. Complete disruption of at least one collateral and both cruciate ligaments is necessary before laxity in full extension is apparent. In a combined MCL/ACL injury, the ACL reconstruction can wait until the MCL heals and when ROM and swelling normalise. Medial meniscal tears occur in only 8% of combined MCL/ACL injuries because of the different mechanism of injury: the ligament injury is caused by excessive opening of the medial side of the joint, but injury to the menisci requires compression. In contrast lateral meniscal tears occur in 32% of combined MCL/ACL injuries. This probably explains the high incidence of MRI diagnosis of "bone bruise" (or bone marrow oedema) of the lateral femoral condyle, following an ACL injury. Combined cruciate ligament injuries involving the lateral complex are less common. The lateral complex needs to be repaired surgically within 7 to 10 days, because tissue retraction and scarring will make reapproximation difficult. Also, the incidence of some peroneal nerve dysfunction is relatively high with this type of multiligament injury.

Knee Dislocation

This is a relatively rare but serious and clinically obvious injury which requires immediate X-ray and reduction under anaesthetic. A knee dislocation is almost always amenable to closed reduction. By default knee dislocation results in a major injury to almost all ligaments, and damages the posterior capsule severely. More importantly, a knee dislocation damages major blood vessels, in up to 40% of cases, and a peroneal nerve in approximately 25% cases. Knee stability, once the knee is reduced, is of secondary importance in the initial management of this injury. It is imperative to check on the integrity of femoral, popliteal and tibial vessels immediately. Doppler measurements are necessary for the initial assessment (manual “feel” of distal pulses is not good enough because of the widespread tissue oedema and the presence of extravasated blood proximally). If there are any doubts about the distal circulation, an urgent arteriogram should be requested. It is also important to immobilise the limb in 30 degrees of flexion, but not with plaster cylinder. It is even more important to monitor distal circulation very closely for several days. Although the initial injury may have not damaged the integrity of major femoral or popliteal arteries, intimal damage may cause the obstruction of the lumen several days later. This is why it is important to monitor the distal circulation very closely and to record the presence or absence of distal pulses very frequently, and to request a repeat Doppler scan or arteriogram, before the patient is discharged. Urgent orthopaedic surgery is usually not required, unless there are associated intraarticular fractures or extraarticular fractures close to the joint. The exception is a posterolateral dislocation of the knee which may not be reducible by closed means due to the button-holing of the medial femoral condyle through the medial retinaculum (these often present with a characteristic invagination of tissues at the medial joint line).

Recently published studies have raised the question of whether arteriography is warranted in the evaluation of multiligamentous injuries of the knee. The objective of this study was to report the frequency of associated vascular injuries in the multiligament-injured knee and examine the role arteriography plays in the treatment protocol. A retrospective analysis was performed on 71 patients over a 12-year period who had a diagnosis of multiligamentous injury of the knee with a tibial-femoral dislocation documented based on physical examination and magnetic resonance imaging findings. Of 72 knee injuries involving multiple ligaments, 12 vascular injuries were identified. Four knees were found to have a vascular injury at initial presentation based on abnormal physical examination and confirmed with arteriography. Eight patients with a vascular injury had normal pulses. Routine arteriography discovered an intimal injury of the popliteal artery in 5 of these patients. Arteriography in the remaining 3 patients was interpreted as normal. These findings suggest that physical examination alone is not sufficient in detecting the majority of vascular injuries after a suspected knee dislocation.

Further information:

- E. Barry McDonough Jr, MD and Edward M. Wojtys, MD. Multiligamentous Injuries of the Knee and Associated Vascular Injuries. The American Journal of Sports Medicine. First published on October 8, 2008.

Extensor Mechanism Injuries

Traction injuries to the extensor mechanism can produce lesions in

the quadriceps and patellar tendons. Inability to perform a straight

leg raise indicates a complete disruption of the extensor mechanism.

Quadriceps Tendon Rupture: complete ruptures of the quadriceps

tendon typically occur in people in their 40s and 50s, usually with

pre-existing degenerative changes in the tendon. On examination, the

patient is unable to actively extend the knee, and a palpable gap can

be detected above the patella. Complete quadriceps tendon rupture requires

surgery.

Patellar Tendon Rupture: these injuries occur infrequently,

and are generally seen in the younger athletic population. This injury

is often overlooked! As with a quadriceps tendon rupture, patients are

unable to do active SLR, but with less obvious soft-tissue disruption.

However, lateral radiograph is required for this injury, as it shows

patella alta. Again, this injury requires repair and reconstruction

of the tendon and retinacula. The lesion in partial rupture of the patellar

tendon is typically located in the posterior half of the tendon at its

insertion site into the patella. Quite often, this injury is a consequence

of overuse in an athletes who participate in repetitive jumping activities.

Site last updated on: 28 March 2014

|

[ back to top ]

Disclaimer: This website is a source of information

and education resource for health professionals and individuals

with knee problems. Neither Chester Knee Clinic nor Vladimir Bobic

make any warranties or guarantees that the information contained

herein is accurate or complete, and are not responsible for

any errors or omissions therein, or for the results obtained from

the use of such information. Users of this information are encouraged

to confirm the accuracy and applicability thereof with other sources.

Not all knee conditions and treatment modalities are described

on this website. The opinions and methods of diagnosis and treatment

change inevitably and rapidly as new information becomes available,

and therefore the information in this website does not necessarily

represent the most current thoughts or methods. The content of

this website is provided for information only and is not intended

to be used for diagnosis or treatment or as a substitute for consultation

with your own doctor or a specialist. Email

addresses supplied are provided for basic enquiries and should

not be used for urgent or emergency requests, treatment of any

knee injuries or conditions or to transmit confidential or medical

information. If you have sustained a knee injury or have a medical condition,

you should promptly seek appropriate medical advice from your local

doctor. Any opinions or information,

unless otherwise stated, are those of Vladimir Bobic, and in no

way claim to represent the views of any other medical professionals

or institutions, including Nuffield Health and Spire Hospitals. Chester

Knee Clinic will not be liable for any direct, indirect,

consequential, special, exemplary, or other damages, loss or injury

to persons which may occur by the user's reliance on any statements,

information or advice contained in this website. Chester Knee Clinic is

not responsible for the content of external websites.

Disclaimer: This website is a source of information

and education resource for health professionals and individuals

with knee problems. Neither Chester Knee Clinic nor Vladimir Bobic

make any warranties or guarantees that the information contained

herein is accurate or complete, and are not responsible for

any errors or omissions therein, or for the results obtained from

the use of such information. Users of this information are encouraged

to confirm the accuracy and applicability thereof with other sources.

Not all knee conditions and treatment modalities are described

on this website. The opinions and methods of diagnosis and treatment

change inevitably and rapidly as new information becomes available,

and therefore the information in this website does not necessarily

represent the most current thoughts or methods. The content of

this website is provided for information only and is not intended

to be used for diagnosis or treatment or as a substitute for consultation

with your own doctor or a specialist. Email

addresses supplied are provided for basic enquiries and should

not be used for urgent or emergency requests, treatment of any

knee injuries or conditions or to transmit confidential or medical

information. If you have sustained a knee injury or have a medical condition,

you should promptly seek appropriate medical advice from your local

doctor. Any opinions or information,

unless otherwise stated, are those of Vladimir Bobic, and in no

way claim to represent the views of any other medical professionals

or institutions, including Nuffield Health and Spire Hospitals. Chester

Knee Clinic will not be liable for any direct, indirect,

consequential, special, exemplary, or other damages, loss or injury

to persons which may occur by the user's reliance on any statements,

information or advice contained in this website. Chester Knee Clinic is

not responsible for the content of external websites.