Knee Problems: Other knee conditions

KNEE PROBLEMS

SURGICAL PROCEDURES

- Acute Knee Effusions

- Baker's Cyst

- Gout

- Pseudogout

- Meniscal Cysts

- Discoid Meniscus*

- Haemarthrosis*

- Pigmented Villonodular Synovitis (PVNS)*

- Osgood-Schlatter Disease

- Tibial Tubercle Avulsions*

- Sinding-Larsen and Johansson Syndrome

- Pes Anserinus Bursitis

- Osteochondritis Dissecans (OCD)

- Bipartite Patella

- Prepatellar bursitis*

- Hoffa's Syndrome or Disease

- Pellegrini-Stieda Disease

* incomplete sections - we are adding more information ...

Acute Knee Effusions

Knee effusions may be the result of trauma, overuse or systemic disease. The most common traumatic causes of knee effusion are ligamentous, osseous and meniscal injuries, and overuse syndromes. Atraumatic etiologies include arthritis, infection, crystal deposition and rarely tumors. For more information please see the following article:

- Michael W Johnson: Acute Knee Effusions: A Systematic Approach to Diagnosis. American Family Physician, April 15, 2000.

Diagnosis and Initial Management of Acute Knee Swelling Recommendations

Laurie Barclay, MD. MedscapeCME Clinical Briefs, 7 January 2010. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:12-19. Abstract

The European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) and the European Federation of National Associations of Orthopaedics and Traumatology have issued consensus recommendations for the diagnosis and initial treatment of patients with acute or recent onset of swelling of the knee. These guidelines are reported in the January 2010 issue of the Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. Clinical context: knee symptoms are common reasons for physician visits, with a lifetime prevalence of up to 54%. Many of these cases reflect symptomatic osteoarthritis, which may occur in 5% to 10% of adults. However, there are many causes of painful swelling of the knee. There are also many approaches to the diagnosis and treatment of these patients. The current guidelines were written in an effort to standardize the diagnostic approach and initial treatment of patients with acute or recent-onset swelling of the knee. A total of 11 rheumatologists and 12 orthopaedists provided expert opinions on the subject, and they focused on knee swelling that had occurred in the past 4 to 6 weeks. Study highlights:

- A clinical examination is the first intervention for a patient with suspected knee swelling. The expert panel noted that many patients with presumed swelling actually had no increase in knee volume, and interobserver agreement regarding swelling of the knee on physical examination is poor.

- Important elements of the patient history in these cases include the speed of onset of swelling, any history of trauma, the characteristics of pain, the presence of fever, the involvement of other joints, recent history of infection, and first vs recurrent episodes of knee swelling.

- Physical examination should include an evaluation of other joints besides the affected knee, including the contralateral unaffected knee. The knee examination should assess the detection of effusion, stability testing, range of motion, and muscular and neurovascular assessment.

- However, the physical examination of the swollen knee alone generally lacks sensitivity and specificity in defining a diagnosis.

- Blood testing is unnecessary for most patients with a swollen knee, unless septic arthritis is strongly suspected.

- In contrast, joint aspiration should be performed among patients with suspected septic, crystal, or inflammatory arthritis. Joint aspiration should not be performed in cases of a possible tumor.

- A plain radiographic study in 2 planes, including a weight-bearing anterior-posterior view, should be performed to evaluate possible fracture or degenerative disease in patients with acute knee swelling.

- There was no consensus regarding including radiographic examination of the unaffected knee in the diagnostic process.

- Ultrasound may be helpful in evaluating possible joint effusion, and other imaging modalities such as MRI may provide details on soft tissue abnormalities.

- Diagnostic arthroscopy is necessary only in rare cases of acute knee swelling, such as when a biopsy is required.

- Every effort should be made to articulate a diagnosis before treatment is initiated, but therapy may begin while the diagnostic process continues.

- Limiting weight-bearing, splints, cold packs, and simple analgesics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications may be used initially for the management of acute knee swelling.

- Antibiotics should not be administered before appropriate diagnostic sampling of the joint fluid, and intraarticular corticosteroids should be held until an appropriate diagnosis has been made and potential contraindications have been ruled out.

- Patients with septic arthritis or those with an onset of swelling within 12 hours should be referred to a practitioner with experience in musculoskeletal diseases. Patients with suspected bone tumors should be seen by an orthopaedist within 1 week, whereas potential inflammatory arthritis should be evaluated by a rheumatologist within 6 weeks.

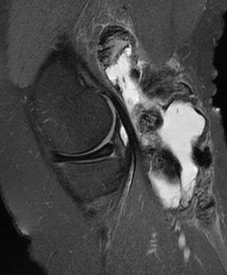

Baker's Cyst (Popliteal Cyst)

A Baker's cyst

(described by Morrant Baker in the 19th century a s a cystic

s a cystic  mass in the popliteal fossae of children) results from knee joint swelling, which causes herniation

of joint fluid and synovium through the capsule of the knee joint posteriorly,

or from distention of the semimembranosus bursa. Most of these cysts

connect into the knee joint. They may also extend downward into the

calf muscles. Causes include rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, and

overuse of the knees. Baker's cysts are often indicative of arthritis

- treatment for the underlying pathology may reduce swelling and permit

resorption. Baker's cyst may be asymptomatic or may cause pain only

with motion or, when inflamed or ruptured, cause continuous discomfort.

On examination, a firm, sometime tender, nonpulsatile mass is usually

palpable in the popliteal space. Because they produce pain and swelling

behind the knee and in the upper calf, Baker's cysts can be mistaken

for deep venous thrombosis (DVT). Because it occasionally can also cause

DVT in the adjacent popliteal vein, a Baker's cyst should be evaluated

with ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Large or chronically

symptomatic cysts can be removed surgically. However, intra-articular

knee problems should also be corrected or recurrence is very likely.

mass in the popliteal fossae of children) results from knee joint swelling, which causes herniation

of joint fluid and synovium through the capsule of the knee joint posteriorly,

or from distention of the semimembranosus bursa. Most of these cysts

connect into the knee joint. They may also extend downward into the

calf muscles. Causes include rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, and

overuse of the knees. Baker's cysts are often indicative of arthritis

- treatment for the underlying pathology may reduce swelling and permit

resorption. Baker's cyst may be asymptomatic or may cause pain only

with motion or, when inflamed or ruptured, cause continuous discomfort.

On examination, a firm, sometime tender, nonpulsatile mass is usually

palpable in the popliteal space. Because they produce pain and swelling

behind the knee and in the upper calf, Baker's cysts can be mistaken

for deep venous thrombosis (DVT). Because it occasionally can also cause

DVT in the adjacent popliteal vein, a Baker's cyst should be evaluated

with ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Large or chronically

symptomatic cysts can be removed surgically. However, intra-articular

knee problems should also be corrected or recurrence is very likely.

Operative treatment of popliteal cysts for refractory symptoms is controversial. If the cyst is secondary to intra-articular pathology, excision of the cyst will not alleviate the pain, and the cyst is likely to recur. Excision of the cyst may be indicated if the pathology within the joint has been corrected but the cyst continues to cause symptoms. Very large cysts involve intricate dissection of surrounding neurovascular structures, and such procedures may be associated with significant postoperative morbidity, including problems with skin healing. Arthroscopic treatment of cysts is also possible. The popliteal recess may be identified and the cyst perforated arthroscopically, obviating the need for open surgery. Long-term results for this procedure are not available, but in our experience the procedure can, in most cases, be done fairly successfully, without additional morbidity.

Further Information:

- Yu WD, Shapiro MS. Cysts and Other Masses About the Knee: Identifying

and Treating Common and Rare Lesions. The Physician and sportsmedicine, July 1999.

Gout

Symptoms: The symptoms of gout include painful swelling and inflammation in one or more of the joints. Gout can be extremely painful and is caused by a build up of uric acid that crystallises in the joints. According to the UK Gout Society, gout affects around one in every 100 people. It's more common in men, particularly those aged 30 to 60, and in older people. The symptoms of gout include: severe joint pain, swelling and warmth around the joint, red and shiny skin around the joint, mild fever, firm white lumps beneath the skin (which are urate crystals or so-called tophi).

Diagnosis: A blood test, looking at urate levels is the best first step. A raised level of urate strongly supports a diagnosis of gout. Examination of the synovial fluid, aspirated from the knee joint or obtained arthroscopically often confirms the diagnosis.

Treatment: Acute attacks of gout are usually treated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). They relieve pain and reduce inflammation. Colchicine tablets should be taken at the very beginning of an attack, until the pain is relieved. Colchicine can also be taken at a dose of 0.5 mg 1–3 times a day to suppress the tendency to gout attacks. The drugs given to relieve an acute attack do not reduce the level of urate in the blood. If attacks become more frequent, or if blood tests show that your urate levels are high you may need one of the urate-lowering drugs. Allopurinol is the most commonly used urate-lowering drug. The commonest cause for ‘failure’ of allopurinol is the patient not taking the drug in the correct dose regularly. The most common side-effect is a rash. Allopurinol can interact with other medication, especially warfarin.

Losing weight, if you need to, is the most effective dietary treatment for gout because it can significantly reduce the urate levels in your body. Avoiding foods that are particularly high in purines may be helpful, whether or not you need to lose weight. Excessive alcohol consumption is associated with gout, and beer is more likely than wines to lead to gout. Drinking plenty of water reduces the risk of urate crystallizing in the joints. Many soft drinks contain large amounts of sugar, in the form of fructose, which is likely to increase the level of urate in the blood. Diet soft drinks are probably a reasonable substitute. Large quantities of strong tea or coffee are also unwise, as they can dehydrate you and may contain purines, which are converted into urate. Cherries seem to be beneficial – either the fruit or the juice, fresh or preserved. However, there’s little evidence for many of the other natural or herbal remedies available for gout. Source: Arthritis Research UK.

Further information

- UK Gout Society: All About Gout. A Patient Guide to Managing Gout. PDF brochure downloaded from: www.ukgoutsociety.org

- Gout. Arthritis Research UK

Pseudogout

Deposits of calcium crystals can cause painful inflammation in or around the joints. When the crystals are in the joint cavity itself they can cause a condition called acute calcium pyrophosphate crystal arthritis or acute CPP crystal arthritis for short. This is often referred to as pseudogout, because it's similar to gout (a condition caused by a build-up of urate crystals). This is particularly common with osteoarthritis of the knee. CPP crystals are present inside the joint cavity and often deposit either in hyaline articular cartilage or menisci (chondrocalcinosis), which why both structures sometime become visible on plain radiographs.

The CPPD crystal deposits that cause pseudogout can also lead to joint damage. Bones in the affected joint or joints can develop cysts, bone spurs and cartilage loss. Further damage can lead to fractures. Joint damage associated with CPPD crystals sometimes mimics the signs and symptoms of osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis. Many people with osteoarthritis have calcium pyrophosphate crystals in their joint cartilage. Also, many people have crystal deposits without having any symptoms. However, acute CPP crystal arthritis is extremely painful, and the affected joint quickly becomes swollen, hot, and tender to touch. The attack starts suddenly, reaching its worst in just 6 to 12 hours. It usually affects only one joint at a time, and is most likely to occur in the knee. The diagnosis of pseudogout is ultimately made when fluid from a joint is examined and when the presence of CPP crystals is confirmed using a polarizing microscope.

The treatment of pseudogout is directed toward stopping the inflammation in the knee joint. Local ice applications, fluid intake (hydration) and resting are helpful initially. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are often first drugs of choice. Cortisone knee injections and oral colchicine are also used. Removing fluid containing the crystals from the knee is often helpful, but arthroscopic washout and joint debridement can reduce pain and decrease the inflammation more rapidly. Long-term prevention of recurrent pseudogout is often best achieved with small daily doses of colchicine.

Further information:

- Calcium crystal diseases (pseudogout). Arthritis Research UK

- Pseudogout. American College of Rehumatology, 2010

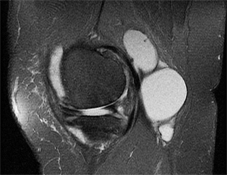

Meniscal Cysts

Meniscal cysts were first described by Ebner in 1904. They are often associated with a specific complex type of meniscal tear called a horizontal cleavage tear, usually of the lateral, rarely the medial meniscus. However, isolated cysts without meniscal pathology have also been reported. Clinically, meniscal cysts look like a small lump, usually at the level of the lateral joint line. The size of the lump often correlates to activity level and the chronicity and the complexity of the meniscal tear. They are encapsulated, hernia-like structures, and they contain viscous synovial, often gel-like, fluid which penetrates through the torn meniscus and accumulates under the skin.

Several theories have been proposed regarding cyst aetiology, including traumatic and degenerative origins. Histology shows a meniscal cyst formation which originates by influx of synovial fluid through microscopic and gross tears in the substance of the meniscus. A meniscal tear with a horizontal component, as well as a tract that provides an exchange of fluid between the joint and the cyst, is often seen. Meniscal cysts are multilocular and lined with synovial endothelial tissue.

Meniscal cysts can be drained with a needle (although this can be difficult because of the viscosity of the content of the cyst) but they will often come back, because a tear in the meniscus will allow further penetration of the synovial fluid into the cyst. The management of a meniscal cyst usually involves an MRI scan of the knee to determine the presence of a meniscal tear and the location of the cyst. In the presence of a meniscal tear, partial arthroscopic meniscectomy followed by arthroscopic cyst decompression is the treatment of choice. If a tear is not confirmed at the time of arthroscopy open decompression of the cyst, performed through a mini-arthrotomy, combined with "outside-in" meniscal repair is the best treatment option. Recurrent meniscal cysts are not uncommon and open cystectomy may be required. In any case, the peripheral meniscal body should be preserved and the meniscus should not be excised under any circumstances.

Clinically lateral meniscal cysts are far more common than the medial ones. However, MR imaging reveals a different pattern. A retrospective review of 2572 knee MRI reports, for the presence of meniscal tears and cysts, revealed that meniscal cysts occur almost twice as often in the medial compartment as in the lateral compartment! Medial and lateral tears occur with the same frequency. These findings, when viewed in the context of the historical literature on meniscal cysts, suggest that MR imaging detects a greater number of medial meniscal cysts than physical examination or arthroscopy, and that MR imaging can have an important impact on surgical treatment of patients. Source: Campbell SE at al. MR Imaging of Meniscal Cysts - Incidence, Location and Clinical Significance. American Journal of Roentgenology 2001; 177: 409 - 413.

|

Lateral meniscal cyst |

Further Information:

- Yu WD, Shapiro MS. Cysts and Other Masses About the Knee: Identifying

and Treating Common and Rare Lesions. The Physician and sportsmedicine, July 1999.

Discoid Meniscus*

A discoid meniscus is a congenital anatomical variant that involves the lateral meniscus significantly more than the medial meniscus. The incidence of this variant in several clinical studies ranges from 0.4% to 17%, while the incidence in a large cadaver study was 5%. The most common symptoms of discoid meniscus, which usually occur during childhood and adolescence, are pain, locking, and a snapping or a clunking sound. These symptoms can occur with both intact and torn discoid menisci. However, symptoms are most frequently a result of a peripheral tear of the central discoid portion of the meniscus. MRI is the modality of choice to evaluate a discoid meniscus before surgery. The traditional treatment for mechanically symptomatic torn discoid meniscus has been a partial arthroscopic meniscectomy, but more recently several authors have reported results of surgical repair. Extensive subtotal or total lateral meniscectomy of the discoid meniscus is best avoided.

Further Information:

- Ralph Di Libero, MD. Discoid Meniscus. eMedicine article, last updated: October 18, 2006.

Haemarthrosis*

In about 80% of cases, rapid development of a large haemarthrosis (blood inside the knee joint) that follows a twisting injury of the knee is due to an ACL injury. Painful, tense effusion usually develops within 15 to 30 min. These patients will have significant hamstring spasm due to swelling and pain, with severely limited range of motion due to pain. Other acute injuries resulting in intra-articular bleeding, which is a bit slower, involve peripheral meniscal tears, patella dislocation, and osteochondral fractures.

Pigmented Villonodular Synovitis (PVNS)*

Pigmented villonodular synovitis is a condition that affects the knee joint. It can also occur in the hip, shoulder, ankle, elbow, hand or foot. When you have PVNS, the lining of a joint becomes swollen and grows. This growth harms the bone around the joint. The lining also produces extra fluid that can cause swelling and make the joint hurt. PVNS isn't common. It usually affects people 20 to 45 years old, but it can also occur in children and people over 65 years old. It may happen slightly more often in men. The cause of PVNS is unknown: it doesn't seem to be caused by certain jobs or activities, and doesn't seem to run in families.

Osgood-Schlatter Disease

Osgood-Schlatter disease, or tibial osteochondrosis, is the most common traction apophysitis and exertion injury in the adolescent knee. In boys, it appears at about age 13 or 14 years, although it can appear anytime between ages 10 and 15 years. In girls, it appears usually at age 10 or 11 years, and the onset ranges from age 8 to 13 years. The incidence is much higher in athletic adolescents and up to 33% of cases are bilateral.

|

|

Clinically, a hard bump at the lower end of patella tendon is often quite obvious. The condition develops from repetitive microtrauma to the tibial tubercle apophysis, usually in jumping sports. Symptoms include an insidious onset of a low-grade aching of the tibial tubercle, that is associated with activity. The pain is relieved with rest and aggravated by acceleration and deceleration forces, such as sudden stopping during running and jumping. Pain is reproduced with resisted extension from 90 degrees of flexion. Plain radiographs are usually normal, but occasionally fragmented bone and ossicles are present, but these may or may not correlate with symptoms.

Initial treatment involves activity limitations and relative rest for 2 to 3 weeks. Patients should avoid sports and activities that require running, jumping or kneeling, until all symptoms are resolved. Cross training with cycling, stair-stepping and swimming should be encouraged, if these activities do not cause pain. Hamstring stretching and a patellar tendon strap may help. Cryotherapy is useful in controlling pain and swelling after activity. Anti-inflammatory pain medication usually does not help in this age group. A corticosteroid injection is contraindicated because the aetiology is not inflammatory, and a steroid injection can result in skin problems and weakening of the tendon. Surgical treatment is an option, but outcomes are very variable and the efficacy is questionable. Both the patient and parents should be aware that it may take a year or two for symptoms to resolve. Up to 60% of patients may continue to have some symptoms. However, symptoms are self-limiting and usually stop when growth stops.

Further Information:

- AAOS patient information brochure: Osgood-Schlatter Disease

- E J Wall. Osgood-Schlatter Disease: Practical Treatment for a Self-Limiting Condition. The Physician and sportsmedicine, March 1998.

- R C Meisterling, E J Wall, M R Meisterling. Coping With Osgood-Schlatter Disease. The Physician and sportsmedicine, March 1998.

Tibial Tubercle Avulsions*

Avulsions of the tibial tubercle are rare, but occur trough its open physis, as a result of a violent quadriceps contraction, usually during jumping activities. Typically occur in male population in 14 to 16 year age group, nearing the end of their growth. Up to 40% of patients in this group have pre-existing Osgood-Schlatter’s.

Sinding-Larsen and Johansson Syndrome

Sinding-Larsen and Johansson is the correct name for this syndrome (not Sinding Larsen Johansson or Sinding-Larsen-Johansson). It is named after Norwegian physician Christian Magnus Falsen Sinding-Larsen and Swedish surgeon Sven Christian Johansson.

Synonyms: apophysitis of the distal pole of the patella, patellar osteochondrosis, adolescent patellar chondromalacia, juvenile osteopathia patellae, osteochondritis patellae juvenilis.

The aetiology appears to be a traction tendinitis with de novo calcification in the proximal attachment of the patellar tendon, which had been partially avulsed. Sinding-Larsen and Johansson syndrome is an overuse traction apophysitis caused by repetitive microtrauma at the insertion point of the proximal patellar tendon onto the lower patellar pole. The lesion is felt to be due to a traction phenomenon in which contusion or tendinosis in the proximal attachment of the patellar tendon can be followed by calcification and ossification, or in which minor patellar fracture or partial avulsion produces one or more distinct ossification sites. Classified by some among the aseptic necroses of bone. This condition is most common in adolescents (prevalent in boys) from age 10 to 14 years who participate in jumping sports. It is the children’s equivalent of patellar tendinosis (jumper’s knee).

Common Signs and Symptoms: pain and tenderness over inferior pole of patella precipitated by overstraining or trauma. Infrapatellar pain and limping are frequent symptoms. Slightly swollen, warm, and tender bump just below the kneecap, pain with activity, especially when straightening the leg against force (such as with stair climbing, jumping, deep knee bends, or weightlifting) or following an extended period of vigorous exercise in an adolescent. In more severe cases, pain during less vigorous activity.

Imaging: usually accompanied by radiographic evidence of osseous fragmentation of the distal patellar pole. Ultrasound scan can give valuable information about the involvement of bone, cartilage and patellar tendon: the lower pole of the patella is often irregular, fragmented, with chondral changes and thickening at the insertion of the patellar tendon. Ultrasonography is also suitable for periodical follow-up of the course of the disease. Typical MR imaging findings include thickening of the tendon with increased signal intensity on T1- and T2-weighted images. As in Osgood-Schlatter disease, fragmentation can occur at the inferior patellar pole.

Treatment Considerations: initial treatment consists of ice (cryotherapy) to relieve pain, stretching and strengthening exercises, and modification of activities. Kneeling, jumping, squatting, stair climbing, and running on the affected knee should be avoided. The exercises can all be carried out at home for acute cases. Chronic cases often require a referral to a physiotherapist or athletic trainer for further evaluation and treatment. A patellar band (brace between the kneecap and tibial tubercle on top of the patellar tendon) may help relieve symptoms. The natural duration of the disease lasts approximately 3 to 12 months.

Pes Anserinus Bursitis

Of the more than 150 bursae in the body, at least 12 bursae are found in each knee, including the suprapatellar, prepatellar, infrapatellar, gastrocnemius, semimembranosus, sartorius and anserine bursae, the No-Name-No-Fame bursa (located at the anterior border of the MCL), and 3 lateral knee bursae located adjacent to the fibular collateral ligament and popliteus tendon laterally.

Pes anserinus is the anatomic term used to identify the insertion of the conjoined tendons into the anteromedial proximal tibia. From anterior to posterior, pes anserinus is made up of the tendons of the sartorius, gracilis, and semitendinosus muscles. The term literally means "goose's foot," describing the webbed footlike structure. The conjoined tendon lies superficial to the tibial insertion of the medial collateral ligament (MCL) of the knee. The muscles of the pes anserinus (ie, sartorius, gracilis, semitendinosus) are each supplied by different lower extremity nerves (ie, femoral, obturator, tibial, respectively). The sartorius, gracilis, and semitendinosus muscles are primary flexors of the knee. These 3 muscles also influence internal rotation of the tibia and protect the knee against rotary and valgus stress.

Pes anserine bursitis is an inflammatory condition of the medial knee, especially common in certain patient populations, often coexisting with other knee disorders. Theoretically, bursitis results from stress to this area (eg, stress may result when an obese individual with anatomic deformity from arthritis ascends or descends stairs). Pathological studies do not indicate whether symptoms are attributable predominantly to true bursitis, tendonitis, or fasciitis at this site. Furthermore, panniculitis at this location has been described in obese individuals. Pes anserine bursitis is most common in young individuals involved in sporting activities and obese middle-aged women. This condition also is common in patients aged 50-80 years who suffer from osteoarthritis of the knees.

Pes anserine bursitis can result from acute trauma to the medial knee, athletic overuse, or chronic mechanical and degenerative processes. An occurrence of pes anserine bursitis commonly is characterized by pain, tenderness, and local swelling. The hallmark clinical finding is pain over the proximal medial tibia, at the insertion of the conjoined tendons of the pes anserinus, approximately 2-5 cm below the anteromedial joint margin of the knee. MRI is the preferred imaging technique.

Rest and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are first-line treatment. Physical therapy is beneficial and often is indicated for patients with pes anserine bursitis. Injection with anesthetic with or without corticosteroid may be helpful. Aspiration of the bursa usually is not required. Surgical intervention is required only rarely. Medical literature continues to report underrecognition of this disorder as a cause for medial knee pain in various groups of patients.

Further Information:

- Glencross PM, Little JP. Pes Anserinus Bursitis. eMedicine article,

Last Updated: March 28, 2006.

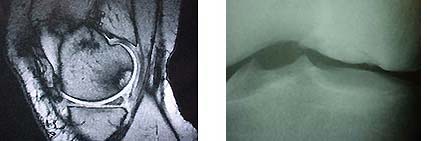

Osteochondritis Dissecans (OCD)

OCD is a focal area of detached or semidetached subchondral bone with hyaline articular cartilage on top. OCD is most commonly located on the lateral aspect of the medial femoral condyle or on the weightbearing surface of the posterior lateral femoral condyle. Although other parts of the condyles and the patella can be involved, only one lesion usually is present. OCD is a common cause of loose bodies within the joint. This disorder usually arises in an active adolescent or a young adult. It is three times more frequent in men than women. Osteochondritis dissecans results from a loss of the blood supply to the subchondral bone, which may undergo avascular necrosis (degeneration from lack of a blood supply). This may be caused by the disruption of end arterioles to subchondral bone from repetitive microtrauma, resulting in local areas is ischemia. A history of local trauma is present in 46% of patients. The affected bone and its hyaline cartilage cover gradually loosen and cause pain. If spontaneous healing doesn't occur, cartilage eventually separates from the bone and a fragment breaks loose into the knee joint, causing locking of the joint, weakness, and sharp pain. An x-ray, MRI, or arthroscopy can be used to diagnose osteochondritis dissecans.

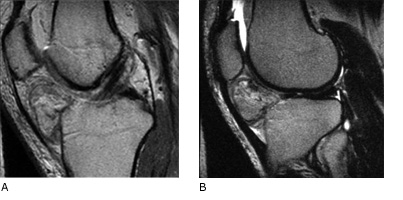

MRI and x-ray appearance of femoral OCD lesion

If cartilage fragments have not broken loose, it may be possible to fix them in place with resorbable pins that are sunk into the cartilage. Earlier attempts to fix chondral or osteochodral fragments with metal pins or screws were often followed by further complications due to migration of metalwork and the damage to tibial articulating surface. If fragments are loose, the surgeon may scrape down the cavity to reach vascular bone, add a bone graft and fix the fragments in position. However, quite often the fixation of osteochondral fragment is not successful. Loose bodies (chondral or osteochondral fragments) should be removed, and the cavity is usually drilled (microfracture technique) to stimulate new growth of cartilage. If the fragments are large and the cavity is in the weightbearing area, the long term prognosis may be poor. Research is currently being done to assess the long-term outcomes of allografts and autologous chondrocyte transplants (with or without bone grafting) to repair the osteochondral cavity.

Traumatic femoral OCD lesion. Xray and arthroscopic images of failed repair with two Herbert screws.

Further Information:

- Kevin G Shea, et al.: Osteochondritis Dissecans of the Knee. AOSSM Sports Medicine Update, March/April 2013.

- ROCK (Research in OsteoChondritis of the Knee), OCD Study Group North America. Jupitoor Project

- B M Ralston, et al. Osteochondritis Dissecans of the Knee. The Physician and sportsmedicine, June 1996.

Bipartite Patella

A bipartite patella has an additional bony fragment connected to the body of the patella by a line of cartilage (synchondrosis). The incidence of biparite patella is 2% to 3%. It is usually an incidental finding on radiographs, and approx. 50% of population with this condition will have the condition bilaterally. Only 2% of patients will have symptoms, usually during adolescence. The most common complaint is anterior pain, and stair climbing or other activities may result in occasional catching. Pain usually begins with the repetitive microtrauma of sports activites or acute trauma. Symptoms are usually due to an incomplete fracture, which may act like a symptomatic non-union. The natural history of the bipartite patella is not clear but seems to be self-limiting.

Prepatellar Bursitis*

Plumbers, carpet layers and other people who spend a lot of time on their knees often experience swelling in the front of the knee. The constant friction irritates a small lubricating sac (bursa) located just in front of the kneecap (patella). The bursa enables the kneecap to move smoothly under the skin. If the bursa becomes inflamed, it fills with fluid and causes swelling at the top of the knee. This condition is called prepatellar bursitis.

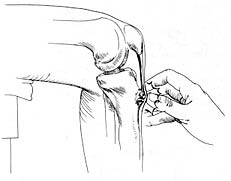

Hoffa's Syndrome or Disease

(named after German surgeon Albert Hoffa, 1859-1907)

An obscure cause of anterior knee pain resulting from impingement

and inflammation of the infrapatellar fat pad, was first reported by Albert Hoffa in 1904. This

condition is characterized by traumatic and inflammatory changes occurring

in the infrapatellar fat pad in young athletes, which may lead to pain,

swelling and restricted motion of the knee. Hypertrophy of the fat

pad may cause it to become trapped between the tibia and femur when

the flexed knee is extended suddenly. Eventually fibrosis may ensue.

On MR images, acute findings indicate the presence of fluid and chronic

findings resemble those of scarring after knee arthroscopy. In some

patients, rupture of the overlying synovial fold and haemarthrosis

may occur after an injury to the infrapatellar fat pad.

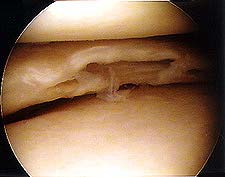

|

Fat pad: Sagittal proton density (A) and T2-weighted (B) MR images of the knee demonstrate distortion and distension of Hoffa's fat pad. Both low and high signal intensity stranding of the infrapatellar fat is demonstrated. Source: Medcyclopaedia TM, www.medcyclopaedia.com,

|

Hoffa's fat pad disease is characterised by chronic knee pain which

is mainly infrapatellar. Acute cases are generally post-traumatic: the

clinical picture includes anterior pain and functional problems, often

in the presence of effusion. In chronic cases, recurrent swelling, infrapatellar

discomfort and knee weakness are the usual features. Clinically, Hoffa's

syndrome is difficult to diagnose, but Hoffa's test can be quite helpful:

with the patient lying on the couch, and with the examiner standing

by the patient's knee, the examiner takes up the bent knee, pressing

the thumbs of both hands deeply along the sides of the patellar tendon

just below the patella. The patient is then instructed to straighten

the leg. This causes pain behind the tendon, in the fat pad region.

Extending a flexed knee tenses the patellar tendon across the fat pad

and elicits a sharp pain. MRI is generally very helpful: it clearly

depicts Hoffa's infrapatellar fat pad and its findings may suggest Hoffa's

syndrome. MR imaging is also important as routine arthroscopy does not

visualize the fat pad well enough and it does not give sufficient morphological

and intrinsic information.

The infrapatellar fat pad of Hoffa is commonly injured but rarely discussed in the radiological literature. Abnormalities within it most commonly are the consequences of trauma and degeneration, but inflammatory and neoplastic diseases of the synovium can be confined to the fat pad. The commonest traumatic lesions follow arthroscopy, but intrinsic signal abnormalities can also be due to posterior and superior impingements syndromes and following patellar dislocation. Infrapatellar plica syndrome may also be traumatic in aetiology. The precise aetiology of ganglion cysts is not understood - the principal differential diagnosis is a meniscal or cruciate cyst. Hoffas fat pad contains residual synovial tissue, meaning that primary neoplastic conditions of synovium may originate and be confined to the fat pad. Inflammatory changes along the posterior border of the pad may also be used to help differentiate effusion from acute synovitis on unenhanced MR examinations.

- Source: D Saddik, E G McNally, M Richardson. MRI of Hoffa's fat pad. Skeletal Radiology, August 2004, 433-444.

A possible relationship between impingement of the infrapatellar fat pad and the development of ossifying chondroma may exist. Since the initial description in 1904, the clinical and pathological processes with an acute-to-chronic progression have been defined. Despite reports of eventual fibrocartilaginous transformation and ossification of the fat pad, no relation has been described between chronic impingement and the development of ossifying chondroma. Authors of this article present a case of a unilateral, ossifying chondroma in the infrapatellar fat pad that resulted from chronic impingement and repetitive microtrauma. This case shows the radiologic, histologic, and pathologic features of Hoffa's disease. Successful arthroscopic resection is presented.

- Source: Krebs VE, Parker RD. Arthroscopic resection of an extrasynovial ossifying chondroma of the infrapatellar fat pad: end-stage Hoffa's disease? Arthroscopy Journal, June 1994.

Pellegrini-Stieda Disease

(named after Italian surgeon Augusto Pellegrini, born 1877 and German surgeon  Alfred Stieda, 1869 - 1943)

Alfred Stieda, 1869 - 1943)

Pellegrini-Stieda disease is an ossification of the medial collateral ligament (MCL) at its femoral insertion usually due to trauma with subsequent hemorrhage. Clinically there is swelling, pain, and tenderness on pressure over the proximal medial femoral condyle. Several weeks after the initial swelling, a calcified mass may be palpated in the region of the medial collateral ligament. Radiographically Pellegrini-Stieda disease appears as a calcification of the proximal portion of the medial collateral ligament, usually consistent with a chronic medial collateral ligament tear.

Pellegrini-Stieda disease is a particular form of myositis ossificans that occurs when the medial collateral ligament of the knee is totally avulsed at its origin to the adjacent condyle. Elevation of the underlying periosteum ensures that the associated haematoma has mesenchymal cells enclosed in the ground substance, which assume the characteristics of osteoblasts with subsequent mineralisation and bone formation. This lesion tends to occur in athletic adolescents, more commonly males, and normally resorbs in one year. Source: Medcyclopaedia.

-

Disclaimer: most of the information on this page is based (in modified, abridged or expanded form) on the relevant sections and parts of the text from the textbook: Athletic Training and Sports Medicine, AAOS Rosemont IL, 1999, with kind permission of the Editor, Robert C Schenk, Jr, MD.

Page last updated: 13 May 2018

Site last updated on: 28 March 2014

|

[ back to top ]

Disclaimer: This website is a source of information

and education resource for health professionals and individuals

with knee problems. Neither Chester Knee Clinic nor Vladimir Bobic

make any warranties or guarantees that the information contained

herein is accurate or complete, and are not responsible for

any errors or omissions therein, or for the results obtained from

the use of such information. Users of this information are encouraged

to confirm the accuracy and applicability thereof with other sources.

Not all knee conditions and treatment modalities are described

on this website. The opinions and methods of diagnosis and treatment

change inevitably and rapidly as new information becomes available,

and therefore the information in this website does not necessarily

represent the most current thoughts or methods. The content of

this website is provided for information only and is not intended

to be used for diagnosis or treatment or as a substitute for consultation

with your own doctor or a specialist. Email

addresses supplied are provided for basic enquiries and should

not be used for urgent or emergency requests, treatment of any

knee injuries or conditions or to transmit confidential or medical

information. If you have sustained a knee injury or have a medical condition,

you should promptly seek appropriate medical advice from your local

doctor. Any opinions or information,

unless otherwise stated, are those of Vladimir Bobic, and in no

way claim to represent the views of any other medical professionals

or institutions, including Nuffield Health and Spire Hospitals. Chester

Knee Clinic will not be liable for any direct, indirect,

consequential, special, exemplary, or other damages, loss or injury

to persons which may occur by the user's reliance on any statements,

information or advice contained in this website. Chester Knee Clinic is

not responsible for the content of external websites.

Disclaimer: This website is a source of information

and education resource for health professionals and individuals

with knee problems. Neither Chester Knee Clinic nor Vladimir Bobic

make any warranties or guarantees that the information contained

herein is accurate or complete, and are not responsible for

any errors or omissions therein, or for the results obtained from

the use of such information. Users of this information are encouraged

to confirm the accuracy and applicability thereof with other sources.

Not all knee conditions and treatment modalities are described

on this website. The opinions and methods of diagnosis and treatment

change inevitably and rapidly as new information becomes available,

and therefore the information in this website does not necessarily

represent the most current thoughts or methods. The content of

this website is provided for information only and is not intended

to be used for diagnosis or treatment or as a substitute for consultation

with your own doctor or a specialist. Email

addresses supplied are provided for basic enquiries and should

not be used for urgent or emergency requests, treatment of any

knee injuries or conditions or to transmit confidential or medical

information. If you have sustained a knee injury or have a medical condition,

you should promptly seek appropriate medical advice from your local

doctor. Any opinions or information,

unless otherwise stated, are those of Vladimir Bobic, and in no

way claim to represent the views of any other medical professionals

or institutions, including Nuffield Health and Spire Hospitals. Chester

Knee Clinic will not be liable for any direct, indirect,

consequential, special, exemplary, or other damages, loss or injury

to persons which may occur by the user's reliance on any statements,

information or advice contained in this website. Chester Knee Clinic is

not responsible for the content of external websites.